Seeing is Believing

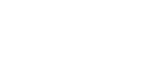

Deb Myers described the relief she felt the first time she watched her husband preach.

Myers, who lives in Frederick, is deaf. Her prior, albeit limited, exposure to church services consisted of watching an interpreter sign in American Sign Language as the minister spoke the words she couldn’t hear. It was a lot of work, exhausting at times, and she didn’t always understand, she said in an interview on Sunday, with her husband acting as an interpreter.

By contrast, she doesn’t have to fight to understand the Frederick Church of the Brethren (FCOB) Deaf Fellowship services led by her husband, the Rev. Peter Myers. She can relax, devoting her attention to the contents of the message being delivered in her own language while worshiping alongside fellow members of the deaf community and their families.

Schools such as Maryland School for the Deaf and Gallaudet University in D.C., combined with federal government jobs, have made Frederick a top destination for deaf students and workers and their families. An estimated 1.2 million Marylanders age 12 and up are deaf or hard of hearing, according to a 2016 annual report by the Maryland Governor’s Office of the Deaf & Hard of Hearing.

While the area has long offered ample opportunities for education and employment for the deaf community, places where deaf people and their families join together in worship in their own language were noticeably absent. Some area churches, including the one Deb Myers attended as a child, offered ASL interpreters for their deaf members to follow along. But the services were still primarily geared to hearing participants, led by a hearing pastor and often characterized by practices that deaf congregants could not participate in, such as long stretches of wordless hymns for which no interpretation was available.

The three families that started FCOB’s Deaf Fellowship in 1971 sought to change that, creating a space where the deaf community’s needs and language were a focus, not a side note. What began as an informal gathering of a handful of people has blossomed into a 100-member fellowship with its own pastor and leadership team, plus Bible studies, Sunday school and other programming.

ASL replaces English words as the means to deliver sermons and sing songs, with an interpreter speaking (or singing) the words for the hearing contingent in the congregation. A projector screen at the front of the worship space shows images and videos to supplement the messages of the sermons. And the people in positions of authority, the altar servers, Bible study leaders, members of the steering committee, are deaf.

Dale Withrow, a Frederick resident and member of the Deaf Fellowship’s steering committee, highlighted the representation of deaf people within church leadership as a crucial difference between a deaf congregation and a hearing church that offers some interpretation or other services for deaf members. “That wouldn’t happen in a hearing ministry,” Withrow said. “You don’t have deaf deacons, deaf altar servers. It’s not intentional, but [deaf] people get left out. When we have a deaf church, they’re running the show.”

The Rev. Bruce Persons, pastor of The Table Church, another deaf congregation in Frederick, probably wouldn’t have pursued his own vocational calling if he hadn’t experienced deaf worship previously, he said in a phone interview using an interpreter service. Persons, like Deb Myers, had limited experience with organized religion as a child.

When he started attending FCOB Deaf Fellowship, he felt he could finally access the information that had long been unavailable. That access, and the knowledge he gained from it, changed his spiritual life and in turn, informed his vocational calling, he said.

Peter Myers is hearing, but uses ASL to communicate with his congregants. Asked if he thought having a hearing pastor detracted from the Deaf Fellowship’s ministry, Withrow said no.

For Withrow, it instead exemplified the way Deaf Fellowship welcomed both deaf congregants and hearing family members into the fold. Interpreters provide the English accompaniment to the ASL sermon and readings, and the projector screens display written versions of biblical passages and song lyrics.

And while Deaf Fellowship operates semi-independently from the larger Frederick Church of the Brethren — “a church within a church,” as Peter Myers described it — members can also participate in programs organized by the larger, hearing church. For example, hearing children of deaf parents can attend the FCOB Sunday school, while hearing parents of deaf children could opt to participate in one of the church’s Bible studies.

It was this immersive, blended cultural and congregational experience that drew the Rosenbarker family to Deaf Fellowship. Parents Rebecca and Cody Rosenbarker are both hearing, while their son, Mikhail, is deaf. They recently moved to Emmitsburg from France, seeking out Frederick specifically because of the educational opportunities for Mikhail, a first-grader at Maryland School for the Deaf. The opportunity to expose their son to the religious background both parents grew up with was an added benefit.

“We’ve really seen him blossom, being in this community where he can interact with other deaf kids and people who speak his language,” Cody Rosenbarker said of Mikhail. Mikhail, who returned to the service Sunday after his first Sunday School class, nodded shyly when asked how he liked the church. In a single class, he had already expanded his vocabulary, learning new words such as “overcome,” he said, with his parents acting as his interpreters.

Services at Deaf Calvary Church in Walkersville, by contrast, cater exclusively to deaf worshippers. The Rev. Chris Hughes, pastor of the church, intentionally wanted a church that was completely “indigenous” to the deaf community — formed, led and funded by deaf people without any dependency on a hearing church. Hughes, who is deaf and was interviewed with his wife acting as an interpreter, also disagreed with Withrow’s conclusion about whether a hearing pastor could lead a deaf congregation. Although he had a good relationship with Myers and with Deaf Fellowship, he stressed the importance of having a pastor who shares the same experience of his or her deaf congregants, both good and bad.

A key difference between deaf congregants and their hearing counterparts, particularly the adults, is their religious knowledge base, Peter Myers said. Hearing adults, even those not raised in a religious family, have some exposure to and understanding of church culture through their day-to-day life. Church culture can be completely foreign to the deaf community, however.

As a result, Bible study groups and informal discussions tend to move at a slower pace, focusing on some of the fundamental concepts and answering members’ questions, Peter Myers said. Certain words and phrases that do not translate directly to American Sign Language muddy the educational waters even further. Even the high education level in the local deaf community doesn’t necessarily carry over to a good spiritual foundation, Hughes agreed. Part of his challenge as pastor is to simultaneously serve both those who have no background in biblical or religious concepts and those who do.

Deb Myers, who herself struggled with some of these words and concepts in her initial introduction, now helps ease the learning process for others as leader of one of Deaf Fellowship’s adult Bible study groups geared specifically to new believers. She emphasized the need not to assume any prior knowledge or take any concepts for granted. Much of the group’s studies focuses on scriptural passages, and applying the biblical context of the messages to modern life, she said through an interpreter.

Despite some differences, Peter Myers described his congregation as, in many ways, not unlike any other hearing church. There are families with young children and older adults, longtime believers and those new to faith, representing different occupations, socioeconomic classes and backgrounds. “Really, our folks are dealing with all of the life issues that are thrown their way, just like everyone else,” Myers said.

Their services, too, include many hallmarks traditional to a hearing church service: biblical passages and a sermon, prayers, offerings and even music. Music is, in fact, a central part of the worship, appreciated on multiple levels and in different ways among congregants, Myers said. Some people who identify as deaf can still hear and can appreciate the melody of the song, Myers said. The meaning behind the lyrics still holds resonance for those who cannot hear the song, while the vibrations from the subwoofer speakers offer a physical way to connect with the music. And just like their hearing counterparts, members of the deaf community also vary in their preferences for worship style and type. The Frederick alternatives to FCOB Deaf Fellowship — The Table Church and another known as Deaf Calvary Church — cater to those different needs and preferences, Persons said.

The Table Church, for example, holds its services on Sunday afternoons, and also includes special programs and outreach catering to children and young adults, Persons said. Deaf Calvary, meanwhile, tends to attract an older crowd, Hughes said through an interpreter.

Persons likened the three options to different flavors, adding that the more choices there are, the better to accomplish the goal he and other deaf pastors have been called to: helping the deaf community to know and love God. Hughes agreed, and said he would like to see even more options for the deaf community to worship. He also highlighted a desire for more collaboration among existing deaf congregations, noting the power in numbers.

By Nancy Lavin. Reprinted with permission of The Frederick News-Post as appearing in the online edition on February 9, 2018.